We did think the sun orbited the earth; some still do apparently. And though I flippantly ended my last post with this, it was pretty serious business.

Nicolas Copernicus, a Polish polymath, announced his discovery of a heliocentric or sun-centered universe in 1543 in his book On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres published just prior to his death. As it turned out, he wasn’t the first (although independently) as Aristarchus of Samos, a Greek astronomer, had discovered the same thing between 310 BC and 230 BC. But after Copernicus, the idea upset the Roman Inquisition and they burned Italian cosmologist Giordano Bruno to death in 1600 for such a heretical idea as a non-earth centered universe. That wasn’t all he was charged with, as he denied several core Catholic doctrines that included eternal damnation, the Trinity, the divinity of Christ, the virginity of Mary and transubstantiation.

Bruno was known to have said just before he died: “Perhaps you who pronounce my sentence are in greater fear than I who receive it.” It’s an ideal quote for the theme of my recent posts challenging what we know and why we know it and the power of an “establishment” in upholding that knowledge, be it accurate or not.

Theology of the day proclaimed the earth as the center of all things. Bruno believed in an infinite universe, a universe where nothing is fixed and everything was relative including time and motion (in 1600 no less). The world is a tiny part of the great unknown and God is a universal mind, found in all things. Bruno's unorthodox views got him in trouble; challenging the status quo got him executed. James Joyce commemorated him in his 1939 novel Finnegans Wake.

So how does this fit into what I said I’d write about language from Cormac McCarthy’s essay “The Kekule Problem” in my last post? (Here is the link if you want to go back). McCarthy wrote that language arrived to help us understand our unconscious. The title of the essay came from August Kekule, a German chemist important to the world of organic chemistry. Legend has it that the ring-shaped molecular configuration of benzene came to Kekule after dreaming (our unconscious) of a snake swallowing its own tail. McCarthy’s essay centered on why it is so difficult for us to understand what our unconscious is trying to tell us if indeed it’s trying to tell us anything. He went on to explain the possibilities of language coming to man as a way of explaining our unconscious.

Before language did a person know that another person even dreamed?

As mentioned previously in this space, I’m also reading the book passed down from antiquity that year after year remains one of the world’s best selling books. That book is The Bible. After watching the popular The Bible series produced by Mark Burnett (the creator of Survivor and The Apprentice) and his wife Roma Downey several years ago, and repeatedly after that, I was fascinated how the stories depicted our behaviour as people and our history. More about this will come in future posts. I started reading The Bible last October at the beginning of the Old Testament and Genesis “In the beginning ...”. Genesis is one of five books that start the Old Testament that are known as the Torah or Pentateuch and attributed to Moses excepting the last eight verses of Deuteronomy where Moses dies. I have reached Psalms (Psalm 130 as of this writing passing the halfway mark which is Psalm 117, the shortest chapter in The Bible and 595 chapters in). I’m reading it like a book from the beginning to the end. All of my previous exposure to The Bible was anecdotal from quotes of verses in chapters spoken of in sermons and different teachings. Many individuals, more knowledgeable and intelligent than I, over many centuries, put this ancient text together in this order. Why wouldn’t I read it like a book? My hunch is that not so many have in our modern times; it’s epic (1189 chapters) and difficult. The book does have a plot and is full of joyful and horrific stories of who we are.

I’ve been using the term “ancient text” in referring to The Bible for a couple of posts now. Briefly this is what I mean. The Bible consists of two volumes, the Old Testament and the New Testament, 66 books in all, 39 in the Old Testament and 27 in the New Testament. The Aleppo Codex (920 AD) and Leningrad Codex (1008 AD) were the oldest known manuscripts of the Old Testament until the 1947 discovery of the Dead Sea scrolls at Qumran that moved the date back another thousand years. Prior to that fragments of the Old Testament text go back to 650 BC with the Ketef Hinnom scrolls. Who knows what more will be discovered. The New Testament has been preserved in more manuscripts than any other ancient work of literature. This is partly why I believe it can serve, combined with the Old Testament, more than the purpose of a religious document but the single most important source to who we are and have come to be. Marcion of Sinope published the first collection of the New Testament books in the second century. In AD 325, the Roman emperor Constantine the Great conducted the First Council of Nicaea to select the books that would remain in the New Testament. In AD 367, Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, canonized the 27 books of the New Testament in use today. Thus my use of the word “ancient.”

Okay, back to where I was on the "Kekule" essay. In my last post, I wrote on our unconscious, one of the two parts that made up McCarthy’s essay and said I would write more about language, the second part, in this one. Here we are.

I might tell you where I’m going with this if I knew but I don’t. For me, it’s an exercise in both thinking and learning. I’ve talked often in conversation about some of the subjects I’m writing about in this space and I was encouraged by a few to write about “it” not knowing quite what “it” is. We’ll see what happens as this is the fourth post about “it” that started with – A Changing Frame Of Reference. The territory of not knowing where the story is going is not so strange to me as most of what I’ve written (i.e. novels, short stories, poetry), I didn’t know where I was going either; I don’t start with the end in mind like some writers do. In fact, I’ve written an article in this space about this if your interested – Don’t Start With The End In Mind.

But back to McCarthy’s “Kekule” essay on our unconscious and the origins of language, and why language landed only on our species of mammal. One might wonder how the two are even connected. That intrigued me. In my last article, I wrote on what McCarthy had discussed on our unconscious; there wasn’t room for language in that article. There were two things that intrigued me on what he said about language. I wrote about the first in Do We Know Why We Know? where he hypothesized that language came to us to help us explain our unconscious. In this posting, I wanted to explore his idea of how language came to us, likening it to a parasite invading a host.

A parasite gets its nourishment from the host. A parasite stays depending on whether the host can harbor the various stages of its development. Parasites cannot survive without a host where as other foreign invaders like viruses and bacteria can. The difference between the history of a virus and that of language is that the virus arrived by Darwinian selection; language has not. We, with our brains, were in no way structured to receive language. There was no place for it; language just found places to fit in.

He writes that language is not a “biological system” as no selection takes place in the evolution of language and there is only one language; the ur-language is the “linguistic origin out of which all languages have evolved.“ Though all languages may evolve from ur-language, we do know that knowing one language doesn’t give one abilities to communicate in any other.

There was no need for language (five thousand other mammals do fine without it) but it is useful for something in us.

From Britannica.com the purpose of language, in most accounts, is to facilitate communication, in the sense of transmitting information from one person to another. But as McCarthy says, why do the other five thousand mammals appear to do fine without it?

Julie Sedivy, a psychology professor at Brown University in Calgary, who has also written for the Nautilus magazine where I discovered McCarthy’s first science non-fiction essay, says, “The purpose of language is to reveal the contents of our minds.”

A thought. I re-read the story of The Tower Of Babel.

Genesis 11:6 reads: “And the Lord said, ‘Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language, and this is only the beginning of what they will do. And nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them.’“

Though the dates are not necessarily consistent could this story be a clue into a rejected attempt for language to come into us. Knowing parasites, God knew what language would do. As a parasitic invasion, language would not come from a good place but still come provided it could feed on the host. Remember Facebook didn't come from a good place either starting at Harvard as a way to compare girls. That didn’t slow its growth.

This also seems like a warning in how success affects us, the invincibility of achievement.

Then the solution in Genesis 11:7: “Come, let us go down and there confuse their language, so that they may not understand one another’s speech.” Here we’re told of the Almighty's intention for us not to understand each other. Was there something more important that we must do? History obviously has demonstrated that language found its way in whether there was room for it or not. I think of the brain as an organ of infinity; there’s always room for things in infinity. Language landed, physically or metaphysically, and we use it—by and large for communicating with each other.

Kind of unbelievable but it took my thoughts in another direction. Mankind has been so keen, especially in the twentieth century, on trying to use evolution to understand who we are and where we came from that maybe we’ve missed something. Something big like our unconscious that we still know very little about. Evolution is incredibly compelling but does have its holes (We'll leave this for a future post.) Is our unconscious just too hard to fathom with the existential tools we have today?

Yet here we are with a language that apparently didn’t come out of need and is not biological but useful. We don’t seem to completely understand the reason it found us, nor exactly what its purpose is and the other five thousand mammals aren’t about to help.

Did human development miss a turn along the way or take a turn off the path we were supposed to be on? Why figure out something we don’t understand when there is so much that we think we do? Is language our portal into our unconscious that we must venture into somehow to learn more even if we don’t know how to?

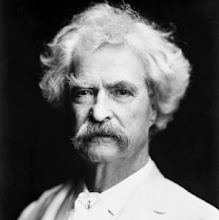

Reminds me of a quote credited to Mark Twain; “What gets us into trouble is not what we don't know. It's what we know for sure that just ain't so.”

Again, my thinking on this has been opened largely by Graham Hancock’s book Fingerprints Of The Gods. But it’s also tweaked another book I remember that I was introduced to as a teen. Immanuel Velikovsky’s book Worlds In Collision, though much refuted and disproved by the science world, brought me maybe a more naive feeling but a nevertheless similar feeling to what Hancock’s did, namely that we don’t have it all figured out and some of what we think we do isn’t right as Mark Twain seemed to recognize. I’ve said before it’s wonderful what science has brought us like computers and mobile phones and the Internet and any piece of music we want to listen to in seconds yet we still struggle with the same questions Abraham did in departing from familiar territory into the unknown. Also, as Hancock wrote, are we “a species with amnesia” which he credits to Velikovsky’s book Mankind In Amnesia?

I wonder whether this is a trajectory familiar to my own experience from science to somewhat identifying with metaphysics and what cannot be reached through objective studies of material reality. Not that science is unimportant because it is important but not when it’s held up as a control or power mechanism preventing the truth from being understood. In The Tower Of Babel it’s like we’re being told that control is not where we’re going to find our answers. When things are under control real answers are not forthcoming. Since the Industrial Revolution, science has been driving things; driving things further into the hands of those in control or in the very least maintaining that control. It’s no wonder we know so little about the mind and our unconscious; we’ve hardly been looking at it, whether through intention or naïveté. The Tower Of Babel seems to tell us we were on the wrong track in building a tower to the heavens yet it didn’t stop us in that pursuit. Maybe we don’t admit we’re building things for the same reason, to get closer to heaven, but we don’t say we’re not either. If anything it’s the ostentation of our power. We seem almost wired to that pursuit. In The Book of John, was he not telling us “the Word” was arriving? As I’ve hazard to suggest previously, did we misunderstand the reason for the Almighty’s arrival as a way to save us from our sins by understanding our unconscious through language “the Word”; a way to fulfill needs inside us by protecting us from ourselves through avoiding the seven deadly sins and living up to the Ten Commandments. Or is this all part of our intended path, and we’re now approaching the epoch of that understanding.

Language was held back in The Tower Of Babel, maybe a first attempt to descend upon us, but not annihilated and like a parasite, as McCarthy writes, it was able to survive and thrive in its host, us, as we found it useful. Then, a way was discovered on how we use it and was written in John, “In the beginning, was the Word.” I am surprised in not having linked The Book of John with the advent of language coming to us to stay, language in the form of our saviour.

The tower was built apparently generations after the flood in the land of Babylonia and interpreted as a time when diverse languages came about. Genesis 11:9 “Therefore its name was called Babel, because the Lord confused the language of all the earth.” Interpretation has Babel being similar to the Hebrew word “balal” which means confusion. Does our unconscious not bring us much confusion? Are there not many interpretations for the teachings found after Christ's arrival?

Again is the Bible written to speak to us from our unconscious or a way into it? Is heaven our unconscious? Was the story of The Tower Of Babel telling us that building a physical tower wasn’t the way into heaven or our unconscious? Was it a foretelling of our unconscious that language wasn’t intended for communication between ourselves or that we even had control of it? Why though? As McCarthy indicates, why make what our unconscious seems to trying to tell us so difficult to understand?

Maybe the intention is not only, not to understand God’s work, Philipians 4:7 “the peace of God surpasses all understanding” but that language was not the means to understand each other as in talking and listening, which we often don’t anyway, but a means to greater understanding of our unconscious and the purpose of the Babel story.

Language wasn’t taken away from us obviously; only we took it as a means to communicate with one another rather than something else that we’ve yet to figure out.

I then received an email from a friend about another Tepe site in Turkey, sister to Gobekli called Karahan. There is more to come, so much more.

That was last Sunday night.

And then hell descended on me. Monday morning my MacBook Pro that I do all my work on, ceased to function for the first time.

* * *

There’s more to come in my next post.

Get yourself a copy of The Actor, The Drive In and The Musician and find out what other readers have already discovered. Follow me on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook or LinkedIn or visit my website at www.douglasgardham.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment